Two containers. They look the same. They both have Hebrew writing. Except, if you look closely, the one on the left is fructose, our sweetener of choice. On the right, you'll find peglax, the Israeli equivalent of Metamucil.

Add Erev Rosh Hashanah. Mix well. And you get the following:

Rena was making challah for Rosh Hashanah. (Don't say it.) She reached for the white canester, which of course contained fructose, necessary to make the challah rise properly. (Don't say it). Little did she realize that yes, instead of taking the fructose, she took the peglax. (There, I said it.) They looked the same. They both have Hebrew and are the same size. And no, we didn't discover her mistake after eating the challah. Long before.

Lesson for today: Don't keep your Israeli laxative in the food pantry.

Now we know.

Shanah Tovah! Have a sweet (and regular) year!

From the Spolters

Monday, September 29, 2008

The Banking Crisis, Teshuvah, and Rosh Hashanah

Even in Israel we hear about the financial crisis plaguing US banks and sending shockwaves around the world. The combination of the devaluation of the dollar combined with the drop in the stock market has especially affected the poorest of Israelis, who count on donations from the US to make ends meet, as noted in this piece in the Jerusalem Post. (And not all of them learn in Kollel. Many are just poor.)

Even in Israel we hear about the financial crisis plaguing US banks and sending shockwaves around the world. The combination of the devaluation of the dollar combined with the drop in the stock market has especially affected the poorest of Israelis, who count on donations from the US to make ends meet, as noted in this piece in the Jerusalem Post. (And not all of them learn in Kollel. Many are just poor.)So, we all breathed a sigh of relief when the US government announced a massive bailout plan aimed at stemming the crisis, relieving the pressure on the banking industry, and returning Wall Street to normal. Many pundits - both political and financial from across the spectrum have come to agree that no matter how distasteful the bailout seems to be, non-intervention on the part of the government would bring even greater pain and calamity than the cost of the bailout.

It sounds true. But the bailout still bothers me - not because of my conservative "small-government" leanings. Rather, the bailout bugs me because of teshuvah - or the lack of it.

Rambam, along with so many other authorities, divide the process of repentance into a series of steps. First, one must regret one's past. Then I have to abandon the sin -- in essence, stop sinning. I must also confess my sin, either before God, if it's a ritual sin, or to my fellow man, if I harmed him in some way. Finally, I must definitively decide to never again return to my sinful ways. I must make a commitment never to transgress that sin again in the future. Without any one of these components, one cannot call himself truly "repentant." There is no real teshuvah. After all, can one truly call himself repentant if he doesn't regret his behavior? Or if he cannot commit himself to change in the future? Each and every component carries critical weight; without it teshuvah is lacking and faulty.

What then is the sin of the banking crisis plaguing Wall Street? Who is the guilty party - the sinner that must repent? While one might want to point the finger at some executive, who made the bad bets that sealed his or her bank's fate, that's only partly true. To my mind, we are all guilty. We're guilty of trying to transform a system designed to foster economic vitality and growth into a monetary printing press. We didn't just want our investments to grow. We wanted them to skyrocket, because normal, slow growth wasn't enough. In essence, we have been guilty of the cardinal sin of greed.

For some reason, I've always been a "buy and hold" kind of investor. My uncle bought me two shares of Dow Chemical for my Bar Mitzvah, and I've still got them. Only now they're six shares and worth several times their original value. But that type of investing doesn't really work right now. You see, investors aren't interested in slow growth; they're interested in meteoric growth. They don't want to know that you've made money for the past forty years. They want to see that you've got a plan to make significantly more money in the near future, or else your stock isn't worth holding on to -- and then it's not worth that much at all.

Shareholders get it, as do corporate executives, so they take steps that might not be in their long-term best interest to spur short-term growth. They front-end their stock options, and don't make plans for a viable long term future. I owned UPS for five years. UPS is a great company; it serves a need worldwide, and makes money year after year. And yet, its stock is worth less now than it was when I bought it. That's the world of investing in which we live today.

Banks got it too. It was not enough to make small profits by lending money to solid potential homeowners. That didn't bring a large enough return. So they started making even larger bets, and enjoying larger returns, a process that only fed upon itself. Until the whole house of cards came crashing down.

I really do feel that this crisis is something that we've all created and fed. Unless we all change fundamentally; unless we change our outlook on work and investing; unless we stop viewing the stock market as some type of slot machine that will safely and reliably keep on making payouts - we will only revisit this crisis again.

Which brings me to my problem with the government's bailout. I really do understand what it's trying to prevent: recession bordering on depression, rising unemployment, widespread misery. Who wouldn't want to avoid such a disaster?

And yet I wonder: Other than that scenario - other than real pain, spread throughout the country, and even the world - what can possibly change the underlying attitude that brought us this crisis in the first place? Where is the teshuvah? Where is the regret about the past? Where is the commitment not to commit the same sin in the future? Sure, the goverment will provide oversight, but how can government even hope to reign in a normal emotion and desire without the need to worry about the consequences?

From another vantage point, the US government is only going to make things worse: all it's really done is shown people that no matter what bad decisions they make; no matter how greedy they get and no matter how much money they lose - it won't be their responsibility. They won't have to pay the price. Someone will step in and save them.

Until someone won't.

I worry about the next time. Where is the US getting the $70 billion to finance this bailout? We're borrowing the money, of course. That's a lot of money to borrow. Who's lending us the money? What's going to happen when someone - or everyone - loses confidence that the US government - the biggest bank of all - can pay back all that money that it owes?

Then we'll have a run on the biggest bank - us - and every other bank as well. And then the "depression" that we're avoiding this year will seem small in comparison, a minor scrape compared to the terrible trauma we will then endure. And the US government will be powerless to prevent it.

I truly believe in the power of pain. No one likes pain, but everyone grows from it. In fact, pain is our most effective symbol of growth. Pain is also our natural radar system, warning us when we're going too far. Imagine a child born without the ability to feel pain. Rather than fortunate, that child must be watched and guarded at all times, because he has no ability to sense just how dangerous his actions might be. What about the parent constantly shielding his daughter from painful situations? Is that protection productive? Hardly, because his daughter never learns how to navigate life situations on her own.

And that's what's happened to us - to American society. In our unwillingness to feel any pain at all; to suffer through the relatively mild pain of a recession, we are losing any ability to sense our own limits. Run out of money? Borrow on a credit card. Maxed out your credit card? Refinance your house. Until no one wants to buy that house, and the bank forecloses. What's going to happen when the foreclosure isn't on Main Street, but on Wall Street?

It sounds depressing. It really is scary. But I cannot see how I'm misreading this situation. Am I missing something? Is there a silver lining? Is there any way that our society of debt - and living beyond our means, both as individuals and as a society - can escape unscathed? I don't see how.

But I sure hope I'm wrong.

Sunday, September 21, 2008

I Did Not Miss Selichot. But What if I Had?

I daven in a shul that has a minyan at 6:30am, followed by a second minyan at 7:30am. Because last night we recited Selichot for the first time at 12:30am, we had no need to arrive early for the morning davening.

I daven in a shul that has a minyan at 6:30am, followed by a second minyan at 7:30am. Because last night we recited Selichot for the first time at 12:30am, we had no need to arrive early for the morning davening.After the first minyan ended, as I sat learning my morning mishnayot, a young boy - he looked about eleven - approached me. Would there be selichot, he asked me, before the 7:30 minyan. I didn't think so, but told him to ask the gabbai. The gabai told him matter-of-factly that because we had recited selichot during the night, there would not be an additional selichot in the morning.

The boy was crushed. Tears began to well in his eyes. He returned to his seat to wait for the second minyan to begin, and began to cry.

"Little boy," I called to him, "Come over here."

I showed him what he could recite from the selichot without the benefit of a minyan - reminding him to skip the י"ג מדות הרחמים - the 13 attributes of mercy of God - that require a minyan. When he learned that he could indeed, recite Selichot, he calmed down, returned to his seat, and began to pray.

And I wondered: what if I had missed selichot this morning - or any morning for that matter? Would I be upset, or would I simply chalk it up as "one of those things - what can you do?" Would I ever be so upset that it could bring me to tears?

I didn't think so.

I've got work to do.

Wednesday, September 17, 2008

A Shopping Trip, Israel and Parshat Ki Tavo

Today Rena and I went shopping. Actually, we went to the bank to get a loan for our car, and truth be told, it was a pretty good experience. The bank gave us a great rate (plus a discount on the loan), and the service was terrific. We waited almost no time, and were dealt with promptly and efficiently. (I know what you're thinking. Yes, this is Israel. Go to Bank Leumi in Kiryat Malachi, and speak to Dani. He's the manager.) While we were signing over and over again, I asked the woman helping us who she got auto insurance with. Not only did she tell me the name and give me the number, she picked up the phone and called them for us. That's Israel. It's like a big family.

Today Rena and I went shopping. Actually, we went to the bank to get a loan for our car, and truth be told, it was a pretty good experience. The bank gave us a great rate (plus a discount on the loan), and the service was terrific. We waited almost no time, and were dealt with promptly and efficiently. (I know what you're thinking. Yes, this is Israel. Go to Bank Leumi in Kiryat Malachi, and speak to Dani. He's the manager.) While we were signing over and over again, I asked the woman helping us who she got auto insurance with. Not only did she tell me the name and give me the number, she picked up the phone and called them for us. That's Israel. It's like a big family.In any event, we had some extra time, so we went to get a cup of coffee. Now in the States, you can also get a cup of coffee, but because it was a kosher coffee shop, we were able to drink our coffee not in the cheap paper cups, but in the glass mugs. It was just a pleasant experience that I really was never able to have in the U.S., and I appreciated being able to have it in Israel.

Then we went to the grocery store, where it's impossible to forget that Rosh Hashanah is coming. You walk into the store and there's a big sign that says, "Shanah Tovah!" The honey display is quite large as well. I even got into a small discussion with a middle-aged man about the sugar-free items in the health aisle of the store.

Finally, on the way out Rena bought a pizza at the store next to the grocery store, and she ended up having a nice discussion with the "secular" guy making pizzas about Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Rena commented on the fact that she never looks forward to Yom Kippur, and that it's a hard day. He told her that he always likes the day, because he feels spiritually cleansed and rejuvinated afterwards.

While each of these little vignettes aren't that special, put together I came away from a simple shopping trip with a great sense of positive warmth. While in America all our efforts go into living a Jewish life - who we congregate with; what we eat; where we go, in Israel, that life surrounds us in so many ways big and small.

All of this caused me to pause at a specific phrase that grabbed my attention from this week's parhsha. Ki Tavo begins with the מקרא ביכורים, the special declaration that each person must make when he brings his first fruits to the Kohen in the Beit Hamidash. Yet, even before he presents the bikkurim to the Kohen, the Torah tells us that,

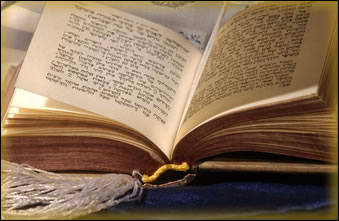

וּבָאתָ, אֶל-הַכֹּהֵן, אֲשֶׁר יִהְיֶה, בַּיָּמִים הָהֵם; וְאָמַרְתָּ אֵלָיו, הִגַּדְתִּי הַיּוֹם לַיהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ, כִּי-בָאתִי אֶל-הָאָרֶץ, אֲשֶׁר נִשְׁבַּע יְהוָה לַאֲבֹתֵינוּ לָתֶת לָנוּ.

וּבָאתָ, אֶל-הַכֹּהֵן, אֲשֶׁר יִהְיֶה, בַּיָּמִים הָהֵם; וְאָמַרְתָּ אֵלָיו, הִגַּדְתִּי הַיּוֹם לַיהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ, כִּי-בָאתִי אֶל-הָאָרֶץ, אֲשֶׁר נִשְׁבַּע יְהוָה לַאֲבֹתֵינוּ לָתֶת לָנוּ.And you shall come to the priest that shall be in those days, and say unto him: 'I profess this day unto the LORD your God, that I have come to the land which the LORD swore to our fathers to give us.'The verse caught my eye because as I was reading it, I felt that I was reading about myself, and my family. כי באתי אל הארץ אשר נשבע ה' לאבותנו לתת לנו - I have come to the Land which God swore to give to our fathers. I truly have. It's exciting and chilling to personalize the words of Torah in such a meaningful way.

But the verse bothered me as well.

Rambam writes that this text is actually part of the ceremony of bringing the bikkurim. The farmer must put the basket of fruit on his shoulder and make this declaration to the Kohen. But this statement made me wonder: What does the farmer mean when he says, "that I have come to the Land which God swore to our fathers to give us"? Is that really true. Truth be told, he was probably born in Israel. He's lived there his whole life. He's never been anywhere else. Why then does he tell God and the Kohen that he has come to the land, when that in fact is untrue?

Kli Yakkar suggests that we cannot really call the Land our own until we have given of it to another. Only when we share the bounty of the land with others can we take ownership over the land that God has given us.

Which, I guess is really the point. The beauty of Israel is really the community; the fact that since everyone here is Jewish, we can, for the most part, eat together. We share holidays together. We wish each other a shanah tovah. We share our health issues with strangers, because we're not supposed to be strangers. And maybe that's when the Land truly becomes ours.

Monday, September 15, 2008

Parshah Questions for Kids - Ki Tavo 5768

Here's this week's PQK. Have a great week!

Here's this week's PQK. Have a great week!

Tuesday, September 9, 2008

Parshah Questions for Kids - Ki Tetze

Here's this weeks PQK. Enjoy!

Here's this weeks PQK. Enjoy!

Thursday, September 4, 2008

Out of the Mouths of Babes

Me: "Hi Leah. How was school today?"

Leah: "Great!"

Me: "Yeah? What did you do?"

Leah: "Well, first we had davening, then we had art and made glue. Then we learned how to cross the street. Then we learned about a rabbi."

Me: "Oh yeah, which rabbi?"

Leah: "Not you."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)