About a year after we arrived in Michigan, Rena and I went out for dinner to celebrate my birthday. We took in a late dinner at Milk and Honey (ob"m), and then decided to head to a movie. I wanted to see the new Spiderman movie and the movie had already been out about two months, so we figured that the theater would be pretty empty.

It was. As we walked in, it was clear that not many people were out to see Spiderman on a Sunday evening eight weeks after its release. Not many - other than the two families from the Young Israel of Southfield (the other Young Israel in Michigan) that were sitting five rows behind us.

"Hey Rabbi! How's it going?" they asked good-naturedly. While I was somewhat taken aback, they didn't seem perturbed that I was in a movie theater.

"Should we call you the Spider-rabbi?" I didn't get it, but I think it was a half-hearted attempt at humor. Looking back, perhaps they themselves didn't expect to end up in a movie with a rabbi, and it was they who were uncomfortable, and not me.

At that moment, I turned to Rena and said, "You know what I just realized? That I can

never do

anything at all anywhere in this community, and not expect the entire communty to know about it."

And I was right - that's just the way it is for shul rabbis.

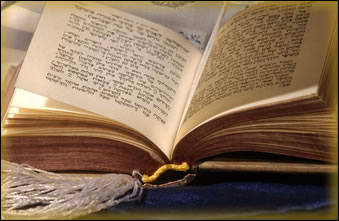

The frightening imagery of the Unetaneh Tokef prayer prominentls highlights the seriousness of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur: "

Who shall live, and who shall die? Who by water and who by fire?" And yet, at the conclusion of the prayer, we find some consolation in the crescendo,

ותשובה, ותפילה, וצדקה מעבירין את רוע הגזרה

And repentance, prayer and charity remove the evil of the decree

(Parenthetically, we should note an important aspect of this phrase: first of all, it does not mean that these three acts remove the evil decree, as many mistakenly believe. If so, the prayer would have said, מעבירין את הגזרה הרעה. Rather, they remove the harshness - the evil of the decree. For a fascinating lecture on this issue and much more about Unetaneh Tokef, listen to

this lecture by my teacher Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter at YUTorah.org)

Most authorities agree that the author of this prayer derived the highlight from a well-known gemara in Rosh Hashanah (16b):

ואמר רבי יצחק: ארבעה דברים מקרעין גזר דינו של אדם, אלו הן: צדקה, צעקה, שינוי השם, ושינוי מעשה. צדקה - דכתיב +משלי י+ וצדקה תציל ממות, צעקה - דכתיב +תהלים קז+ ויצעקו אל ה' בצר להם וממצקותיהם יוציאם, שינוי השם - דכתיב +בראשית יז+ שרי אשתך לא תקרא את שמה שרי כי שרה שמה, וכתיב וברכתי אתה וגם נתתי ממנה לך בן, שינוי מעשה - דכתיב +יונה ג+ וירא האלהים את מעשיהם, וכתיב +יונה ג+ וינחם האלהים על הרעה אשר דבר לעשות להם ולא עשה. ויש אומרים: אף שינוי מקום, דכתיב +בראשית יב+ ויאמר ה' אל אברם לך לך מארצך, והדר ואעשך לגוי גדול ואידך - ההוא זכותא דארץ ישראל הוא דאהניא ליה.

Said Rabbi Yitzchak: four things rend apart a man's decree, and they are: charity, crying out, changing of one's name, and changing of one's actions. Charity - as it is written, "and charity shall save [one] from death." (Proverbs 10) Crying out - as it is written, "and they cried out to God in their anguish, and from their desperation he removed them." (Psalms 107) Changing of the name - as it is written, "Your wife Sarai, her name shall no longer be Sarai, rather her name shall be Sarah," (Genesis 17) and it is written, "And I shall bless her and I will also grant her a son." Changing of one's actions - as it is written, "And the Lord saw their actions," (Jonah 3) and it is written, "and the Lord regretted the evil that He had spoken to do to them and he did not do it." Some also say, even changing one's place, as it is written, "And God said to Avram go forth from your land," (Genesis 12) and then, "and I will make you into a great nation." And the other opinion says, that is the merit of the Land of Israel that helped him.

We readily recognize three out of the four from the prayer: charity and crying clearly refer to charity and prayer from Unetaneh Tokef. Moreover, changing of one's actions seem to signify a sense of repentance - the teshuvah from the prayer. Yet, aside from the fact that the the final two (or one and a half) - change of place and change of name - never appear in the text of Unetaneh Tokef (a subject Rabbi Schacter addresses wonderfully), they seem to challenge our sense of what Teshuvah is all about.

I'd like to focus on one of the two - the change of locations, and ask a simple question; why should the fact that I relocate from one place to another have any bearing on my spiritual standing before God? What difference does it make whether I reside in Oak Park, Michigan, or Silver Spring, Maryland or Yad Binyamin, Israel, if I'm still the same person?

While intellectually the question makes a great deal of sense and I truly had difficulty answering these questions, this year I came to an appreciation for the teshuvah of "changing of one's place." This year I think I understand. I came to realize that teshuvah is much more than an intellectual process. It can encompass a great deal of emaotion turmoil, and probably should.

To what degree do we evaluate and justify ourselves by the way that those around us relate to us? After all, I've lived in a community for a number of years; I've been active and involved, made friends and business relationships. Not only do others know who I am - I know who and what I am by the way that they relate to me. When I walk into shul, or a friend's home or a business, they recognize me, acknowlege me and in a very real sense establish who I am in my own mind. I don't need to search for my place. I have a place both physically but metaphysically as well: I'm the philanthropist (or the tightwad); I'm the shul talker (or the guy who never talks in shul); I never listen to the rabbi's speech (or never miss a word). Everyone expects me to be who they recognize, and I don't disappoint. It's that very sameness - the expectations of those who surround us that keep us constant and steady.

But what if one day you woke up in your own community and no one recognized you. The lady at Starbucks didn't give you your regular cup, because she doesn't know what you want. Would you buy soemthing different, or just the same cup of coffee that you do every day? Probably get the same. But then your secretary didn't know how to handle your emails. And your coworkers didn't know what to expect from you. And your kids didn't know what set you off or made you happy. Would you still act and react the same way you always did? We'd be thrown for a loop, because we'd need to reevaulate our actions, interactions and reactions - because you could no longer take anything for granted.

And what if you had a position in your community, and woke up one day and it was gone. You were just a regular Joe like everyone else. Would you still act the same? Would you still have the same expectations of yourself, and everyone else around you?

That's what happened to me this year.

Perhaps the most difficult aspects of serving as a communal rabbi is the "fishbowl" phenomenon. Everyone's watching you. They're looking at what you do, what you buy, who you greet, who you don't. They see you even when you don't see them, and care not only about what classes you give and hospitals you visit, but what movies you watch - or whether you watch them at all. And while it's really hard to maintain that constant sense of vigilance and attentiveness at all times in public, there's another side to it as well.

You get used to the fact that people know who you are. When you walk into shul, they subtely acknowledge your presence; they're (usually) comforted that you're there. When you walk into a shiva house or hospital, they visibly relax. They wait for you to finish davening in shul, and for you to make kiddush before anyone starts eating. When you visit them for a meal, it's a big deal - an honor.

I don't kid myself. I'm quite aware that it's not me personally - but my position as their rabbi. (Although I do think I'm a good guy also.) But that status - those reactions - become part of your psyche. You assimilate them, not necessarily in an egocentric way, but as a matter of identification. Being a rabbi wasn't just my job - it became in a sense a very real part of my identity, not just for others, but more importantly, for myself.

And then I moved to Isreal, left the rabbinate, and moved to another country. To be honest, people here know that I was a rabbi; I've spoken in shul here, give a regular gemara shiur, given a few classes and answered questions. But even to those people, while I'm a rabbi, I'm not their rabbi. And to most people here and all the Israelis, I'm just a regular person. A nice guy - somewhat knowledgable - but nothing special.

Which is just fine. I like my anonymity. I enjoy dressing casually in shul and around the community. I love not having to look around at the supermarket to make sure that I didn't miss saying hello (and inadvertantly insulting) someone.

But it's also very, very painful. If I'm not "Rabbi Spolter" - if I'm just Reuven Spolter, then while I know who I am, I've lost a very real part of "what" I am. I have to reassess: do I learn enough? What's my place supposed to be in my new community? What is it reasonable to expect of myself?

These are all questions that I never asked myself as a rabbi, because they more or less answered themselves. And they don't anymore. This last Yom Kippur - during davening actually - I finally became aware of the extent of this loss of self-identity and how much it was affecting me. And that's when the questions truly came to the forefront. I think this is part of what the Gemara means when it refers to "change of place." It's that sense of confusion, self-awareness and reevaluation from losing the surroundings you took for granted. It's about asking questions you never thought to ask.

Answering these very questions are the essence of what teshuva is all about. And they don't stop at Yom Kippur.

Yom Kippur is just the beginnning.

Why is it that at times, the thing that we want is probably not very good for us? Like that pint of Ben and Jerry’s? Or Facebook? (After all, do we really need to know what every person we know is doing at every moment of the day? When do “friends” become a distraction?) Yaakov’s fears in Vayigash remind us that sometimes the path towards growth involves traveling the road that we fear the most.

Why is it that at times, the thing that we want is probably not very good for us? Like that pint of Ben and Jerry’s? Or Facebook? (After all, do we really need to know what every person we know is doing at every moment of the day? When do “friends” become a distraction?) Yaakov’s fears in Vayigash remind us that sometimes the path towards growth involves traveling the road that we fear the most.